In the post-pandemic era, the procurement of protective apparel has shifted from a transactional necessity to a strategic operation. For procurement managers and healthcare professionals alike, the challenge is no longer just availability—it is specificity. Selecting the wrong barrier protection can lead to compliance violations, wasted budget, and, most critically, compromised safety for healthcare workers.

This guide dissects the technical criteria required to navigate the complex landscape of the medical sector, ensuring your workforce is protected against biological and environmental hazards.

Understanding Performance Requirements: Why Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Matters

When evaluating personal protective equipment, “safety” is not a vague concept; it is a measurable data point defined by rigorous performance requirements. A coverall is not merely a piece of fabric; it is the final line of defense between a human being and a hazardous agent.

For hospital buyers, understanding the distinction between simple isolation barriers and surgical-grade protection is paramount. The material must balance tensile strength (durability) with barrier efficiency. If the PPE fails under stress or permits fluid strikethrough, it fails its primary purpose.

The Role of Regulatory Bodies in Setting Global Safety Standards

| AAMI Level | Barrier Performance (Fluid Resistance) | Typical Clinical Application | Recommended for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Minimal water resistance | Basic care, standard isolation, visitor coveralls | Low Risk |

| Level 2 | Low water resistance (Spray impact) | Blood draw, suturing, ICU, pathology lab | Low-to-Moderate Risk |

| Level 3 | Moderate water resistance (Splatter) | Arterial blood draw, IV insertion, ER trauma | Moderate Risk |

| Level 4 | Viral & Blood Penetration Resistance(ASTM F1671) | Long, fluid-intensive surgeries, pathogen resistance | High Risk |

Compliance is the bedrock of medical procurement. Regulatory bodies such as the FDA (in the U.S.), the CDC, and OSHA do not merely suggest guidelines; they enforce standards that determine market access and user safety.

- FDA: Classifies surgical apparel based on risk levels.

- ASTM International: Sets the testing methods for fluid and viral resistance.

- AAMI (Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation): Defines the barrier performance levels (Level 1 to 4).

Pro Tip: Always verify that your supplier’s test reports originate from accredited laboratories (like Nelson Labs) and align with current standards set by these regulatory bodies.

Selecting Coveralls for Healthcare Settings: From Infection Control to Surgical Procedures

Healthcare settings are dynamic environments. A coverall suitable for patient triage may be woefully inadequate for the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) or a trauma center. Therefore, infection control protocols must dictate the selection process, matching the specific hazard level of the zone to the PPE specifications.

High-Risk Protection in the Operating Theatre for HCWs (Healthcare Workers)

| Material Type | Fluid Barrier Protection | Breathability (Delta P) | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spunbond PP | Low | High (Very Cool) | Basic hygiene, visitors, dry environments |

| SMS / SMMS | Moderate to High | Moderate (Balanced) | Surgical gowns, prolonged wear in OR |

| Microporous Film (PE Laminated) | High (Liquid Proof) | Low (Can be warm) | High-fluid risk zones, chemical handling |

| Flash Spun (e.g., Tyvek) | High | Low to Moderate | Cleanrooms, pharmaceutical manufacturing |

Scenario: Imagine a trauma surgeon and their team in an operating theatre performing a complex, six-hour orthopedic procedure. The environment is high-stress, and the risk of heavy fluid exposure is constant.

In this scenario, HCWs (Healthcare Workers) face a dual challenge:

- Protection: They need absolute confidence that the gown or coverall will repel high-velocity fluids.

- Comfort (Breathability): They need to prevent heat stress. If the material has a high Delta P (pressure differential), the wearer becomes fatigued, potentially compromising the surgery.

For invasive surgical procedures, procurement must prioritize materials that offer high barrier protection without creating a “sauna effect” for the wearer. Look for microporous films or SMS (Spunbond-Meltblown-Spunbond) fabrics that allow moisture vapor to escape while blocking liquid entry.

Advanced Barrier Protection: Resistance to Blood, Fluid, and Viral Penetration

In high-stakes medical environments, the primary enemy is often invisible. The difference between a standard gown and a high-performance coverall often comes down to its ability to resist blood, body fluids, and viral penetration.

To ensure fluid resistance, verify the product against these key standards:

- ASTM F1670: Measures resistance to synthetic blood penetration.

- ASTM F1671: The gold standard. It measures resistance to viral penetration using a bacteriophage (Phi-X174) as a surrogate for pathogens like Hepatitis B, C, and HIV.

Addressing Splash Resistance in Critical Zones

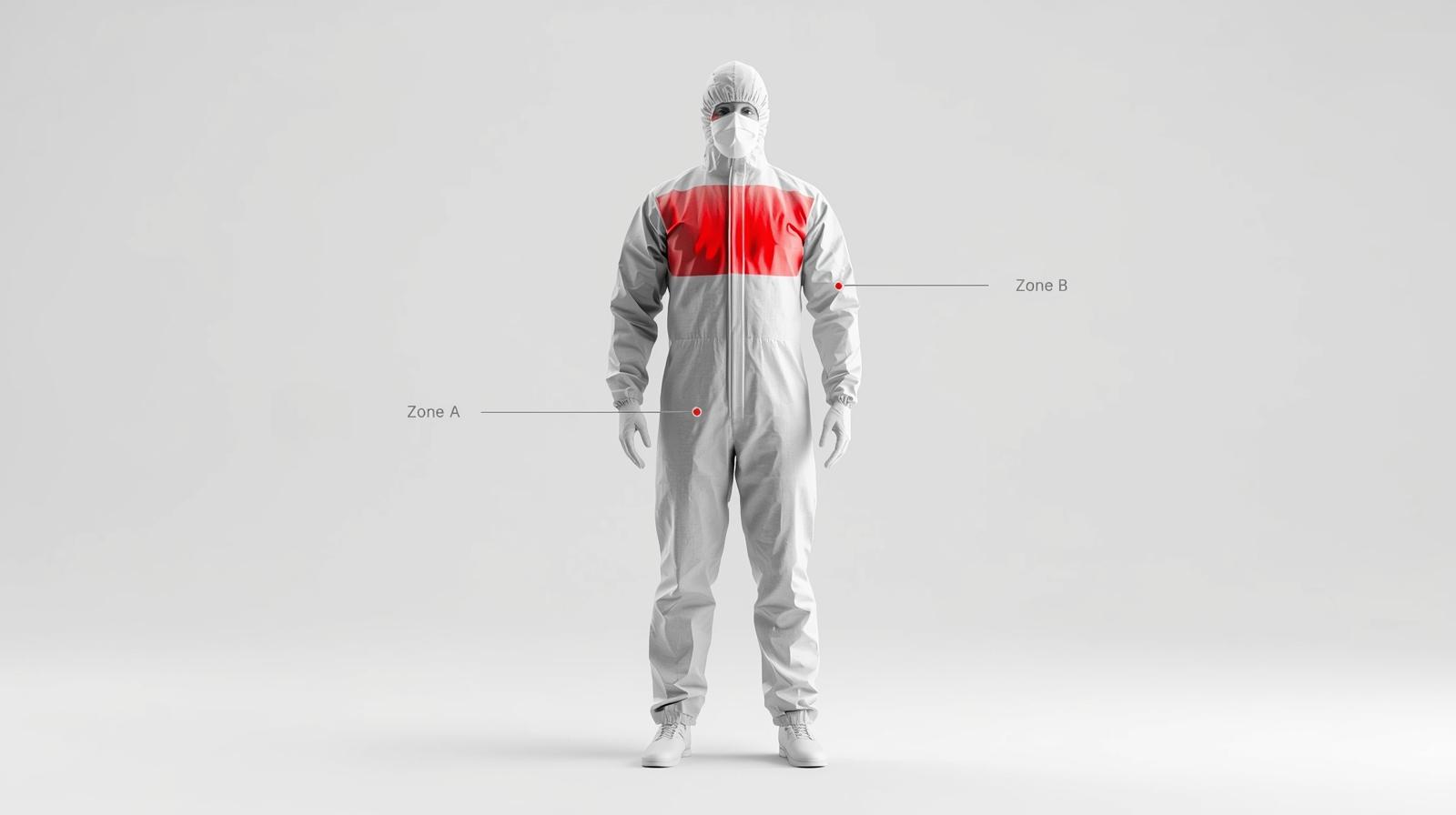

Procurement Checklist: Verifying Critical Zone Integrity when evaluating sample coveralls, inspect these key areas to ensure compliance:

- Seam Construction: Are the seams serged (stitched) or heat-sealed? Note: Only heat-sealed or taped seams offer true viral protection.

- Sleeve Attachments: Check the junction between the sleeve and the body. This is a common failure point for fluid strikethrough.

- Chest Reinforcement: Does the chest area (Zone A) feel thicker or laminated compared to the back panel?

- Cuff Tightness: Are the cuffs elasticized or knitted to prevent fluid from running down the arm during elevated procedures?

Not all parts of a coverall are created equal. The FDA and AAMI standards focus heavily on critical zones—areas where direct contact with blood and body fluids is most likely to occur.

- Zone A (Front of the Chest): High risk of direct splatter.

- Zone B (Sleeves): High risk during surgical manipulation.

Splash resistance in these critical zones is non-negotiable. Many budget-friendly coveralls fail here, offering protection only on the main body while leaving seams or sleeves vulnerable. High-quality PPE will feature:

- Reinforced seams (taped or heat-sealed).

- Additional PE coating or laminate layers in critical areas.

- Hydrostatic pressure ratings that exceed AAMI Level 3 or 4 requirements.

Industry-Specific Applications: From Emergency Medical Services to Manufacturing Processes

| Industry Sector | Primary Hazard | Key Standard to Look For | Recommended Gear Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency Medical Services (EMS) | Bloodborne Pathogens, Roadside Hazards | NFPA 1999 | High tear resistance, full-body coverage |

| Pharmaceutical Mfg. | Particulates, Sterility | Low Linting / Sterile | Cleanroom compatible, autoclave resistant |

| Infectious Disease Control | Viruses (Ebola, COVID-19) | ASTM F1671 / EN 14126 | Taped seams, viral penetration resistance |

| Chemical Processing | Liquid Chemical Splash | Type 3 / 4 (EN Standards) | Chemical barrier film, sealed zippers |

While hospital wards are controlled environments, other sectors require specialized protection strategies.

NFPA 1999 Standards for Emergency Medical Coveralls

For Emergency Medical Services (EMS), the environment is unpredictable—a rainy roadside, a cramped ambulance, or a hazardous industrial accident site. Here, the NFPA 1999 standard is the benchmark.

Unlike standard hospital gowns, coveralls certified to NFPA 1999 are designed to be single-piece garments that provide full-body protection against bloodborne pathogens and environmental hazards. They undergo rigorous testing for physical durability (tear resistance) because EMS personnel are constantly moving, kneeling, and lifting.

Maintaining Sterility and Autoclave Compatibility in Manufacturing Processes

In pharmaceutical manufacturing processes or cleanroom environments, the goal shifts. Here, the PPE is often protecting the product from the worker (skin flakes, hair, bacteria).

- Sterility: Coveralls must be manufactured and packaged in cleanroom environments to ensure they are particulate-free (low linting).

- Autoclave Compatibility: For facilities using reusable garments to reduce waste, the material must withstand repeated autoclave cycles (high-pressure steam sterilization) without degrading the fabric’s barrier properties.

Procurement managers in this sector must look for:

- Polyester continuous filament fabrics (for reusables).

- Tyvek® or similar high-density polyethylene materials (for disposables).

Frequently Asked Questions on Selecting Medical Coveralls

Q1: What is the main difference between AAMI Level 3 and Level 4 coveralls?

A: The primary difference lies in viral resistance. AAMI Level 3 coveralls provide moderate fluid protection against splatter and soaking (passing the hydrostatic pressure test). AAMI Level 4 offers the highest level of barrier protection and must pass ASTM F1671, proving resistance to viral penetration (using bacteriophage Phi-X174). For high-risk surgical procedures involving pathogens, Level 4 is required.

Q2: Why is Delta P important when choosing surgical coveralls for HCWs?

A: Delta P (Differential Pressure) measures the breathability of the fabric. A high Delta P means the material is harder to breathe through, which can cause heat stress and fatigue for healthcare workers during long surgeries. The goal is to select materials like SMS or advanced Microporous Films that offer a safe balance: high fluid barrier efficiency with a manageable Delta P for comfort.

Q3: What are “Critical Zones” in medical gowns and why should procurement managers check them?

A: According to FDA and AAMI standards, Critical Zones are the areas most likely to come into direct contact with blood and body fluids—specifically the front of the chest (Zone A) and the sleeves (Zone B). Procurement managers must verify that these specific zones meet the required barrier performance (e.g., reinforced seams, PE coating), as non-critical zones (like the back) may have lower protection levels.

Q4: Can medical coveralls be reused and autoclaved?

A: It depends on the material and intended use. Disposable coveralls (often made of Tyvek® or SMS) are designed for single use. However, reusable gowns made from polyester continuous filament are designed to withstand repeated washing cycles and autoclave sterilization without degrading. For pharmaceutical manufacturing, ensure the reusable gear maintains low-linting properties after sterilization.

Q5: What standard should I look for when purchasing coveralls for Emergency Medical Services (EMS)?

A: For EMS, the benchmark standard is NFPA 1999. Unlike standard hospital gowns, NFPA 1999 certified coveralls are designed for rugged, unpredictable environments (roadside accidents, ambulances). They are tested for high physical durability (tear resistance) and full-body protection against bloodborne pathogens and environmental hazards.

Q6: Does “Water Resistance” mean the coverall is “Viral Proof”?

A: No. “Water resistance” (often found in Level 1 or 2 gowns) only means the fabric repels liquid spray. It does not guarantee protection against viruses. To ensure protection against viral penetration, the product must explicitly state compliance with ASTM F1671, which tests against biological pathogens. Always check the technical data sheet for this specific standard.

Conclusion: Making an Informed Decision for Your Workforce

Choosing the right coverall is a calculated risk assessment. Whether you are equipping healthcare workers in a Level 1 trauma center or technicians in a sterile compounding lab, the decision must be rooted in data.

By aligning your procurement strategy with regulatory bodies, understanding the nuances of fluid resistance in critical zones, and distinguishing between hospital and industrial needs, you ensure operational continuity. In the medical sector, quality PPE is not an expense; it is an insurance policy for your most valuable asset—your people.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- Medical Gowns. (Current as of 01/2024). Retrieved from FDA.gov.

- Personal Protective Equipment for Infection Control.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Guidance for the Selection and Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in Healthcare Settings.

- Sequence for Putting On and Safely Removing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

- ASTM International

- ASTM F1671 / F1671M – 13: Standard Test Method for Resistance of Materials Used in Protective Clothing to Penetration by Blood-Borne Pathogens Using Phi-X174 Bacteriophage Penetration as a Test System.

- ASTM F2100 – 19: Standard Specification for Performance of Materials Used in Medical Face Masks.

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA)

- NFPA 1999: Standard on Protective Clothing and Ensembles for Emergency Medical Operations.

- Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI)

- ANSI/AAMI PB70:2012 – Liquid barrier performance and classification of protective apparel and drapes intended for use in health care facilities.